World-first research by the University of Sunshine Coast looks at whether legislation to reduce plastic waste is helping our marine life.

The 2017 United Nations Ocean Conference estimated that oceans worldwide could contain more weight in plastics than fish by the year 2050.

World Wide Fund Australia says nearly all species of sea turtles are classified as endangered and plastic is doing more than its share of damage.

Amid a global push to tackle plastic waste, Australia is investing in research, recycling and manufacturing programs to create a circular economy and reduce our reliance on plastics. Most states have introduced bans on the supply and sale of single use plastics to reduce the waste stream.

University of Sunshine Coast (USC) students, led by Associate Professor Kathy Townsend, are looking from an environmental perspective at the legislation and whether it is reducing the detrimental impact of waste to marine animals globally.

In particular, they’re looking at Queensland’s container reuse scheme, a single-use plastic bag ban introduced in 2018 and a ban in September, 2021 of single-use plastics.

“Even a single piece of plastic can kill a turtle,” says Kathy. “Plastic bags are notoriously dangerous for turtles and sea birds who mistake them for food and choke or get tangled among them until they cannot swim or fly.”

In a world-first, live turtles are being studied to see how much plastic they’ve ingested. Previously, the only efficient method to determine what plastics had been ingested relied on accessing sick and injured turtles that ultimately died. Researchers can now use blood and tissue samples to determine the chemical that exists if turtles have been exposed to plastics.

Monitoring waterways

A study by Kathy and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) found that a turtle had a 22 per cent chance of dying if it ate just one piece of plastic. Once a turtle had 14 plastic items in its gut, there was a 50 per cent likelihood that it would die.

The study included a sample of nearly 1000 turtles on beaches around Australia.

“Two of the turtles we studied had eaten only one piece of plastic, which was enough to kill them. In one case, the gut was punctured and in the other the soft plastic clogged the gut,” Kathy says.

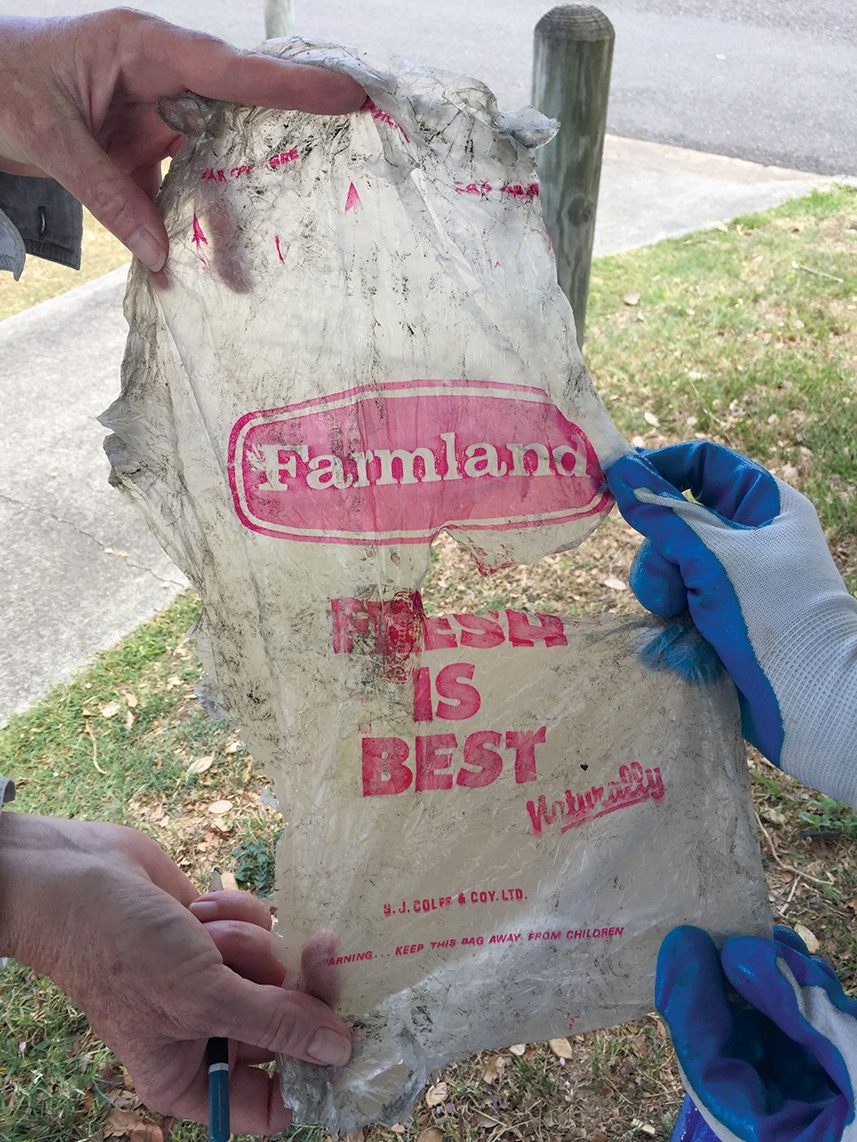

USC researchers began tracking the impact of Queensland’s ban on plastic bags in 2018 by monitoring the marine debris found inside stranded sea turtles from along Fraser Coast beaches and the mouths of the Mary, Susan, Burnett and Burrum rivers.

Kathy says marine debris surveys, conducted every six months, provide an opportunity to measure the success that the ban on single-use plastic bags is having in reducing the amount of plastics ending up in waterways.

Researchers are looking at debris in the environment and comparing it to debris surveys conducted pre-bans. They want to know if there are fewer plastic items in the environment and if so, are fewer showing up in the guts of sea turtles, in particular.

One of the concerns is if new reusable, much heavier-duty plastic bags, which can survive in the environment for a longer time period and never existed pre-legislation, are finding their way into the ocean and impacting on marine life.

Poisoned by plastics

In 2020, USC PhD candidate Caitlin Smith built on the research and began studying the effects of toxic chemicals from ingested microplastics on sea turtles. Her research will quantify the amount of microplastic found in the gastrointestinal tracts of turtles and use biomonitoring tools to calculate the oxidative stress, which can lead to cell and tissue damage from chemical exposure.

“We know that marine turtles are dying from ingesting plastic particles,” Caitlyn says.

“However this is the first study to explore the toxicity of these particles and the health risks to turtles from chemical and heavy metal exposure.

“While plastic can cause blockages in turtle’s intestines and even pierce the intestinal wall causing septicaemia, there may be other factors contributing to deaths.

“The study will look at the correlation between the health of individual turtles to their exposure to debris ingestion, and answer the question of whether poor health is due to the physical presence of debris or its associated toxicity.”